Credit Card Chargebacks

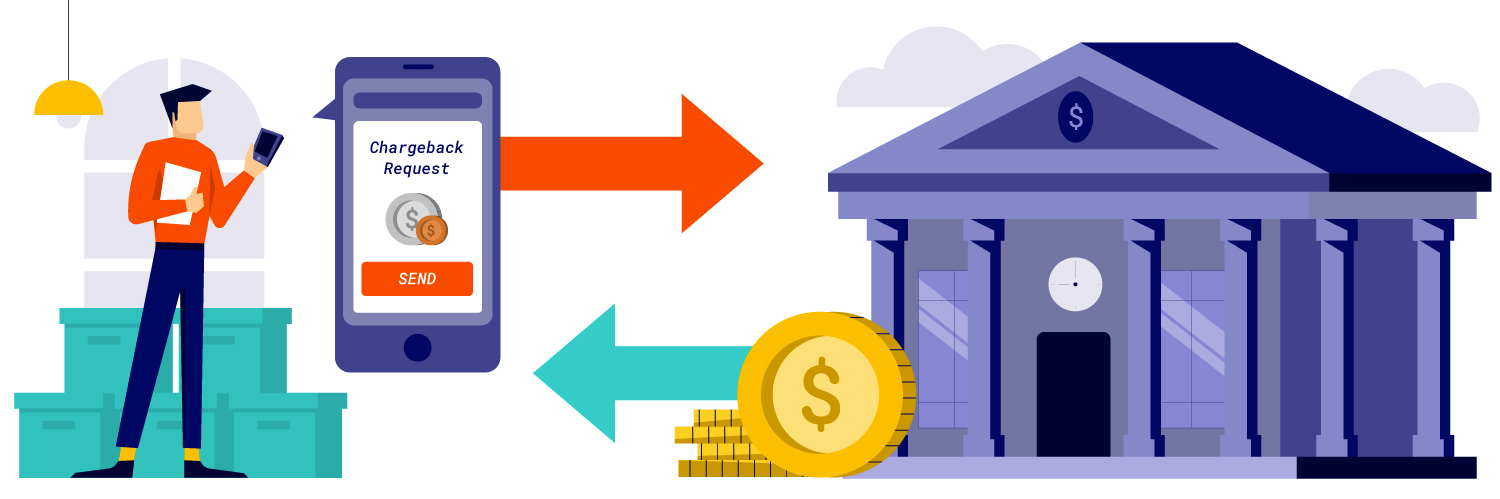

A chargeback is a payment dispute that reverses a credit card transaction and returns the funds from the payment to your customer’s card issuing bank.

Chargebacks are initiated by a cardholder’s issuing bank—typically at the cardholder’s request, and in response to problems like merchant fraud, processing errors, billing errors, or a business’s failure to properly deliver its goods or services.

Basically, the issuing bank evaluates your customer’s chargeback request, determines its validity, and then sends the transaction back to the merchant’s acquiring bank or payment processor to dispute the sale. Your acquirer or payment processor then studies the transaction and makes its own judgment.

If the acquirer believes the chargeback is valid, your payment processor pulls the money for the transaction from your business’s merchant account and refunds the cardholder’s issuing bank. All of this happens after the initial stages of the credit card payment process are complete.

Payments by Corporate Tools Request a Free Consultation

Table of Contents

What is the Purpose of Chargebacks?

Chargebacks essentially level the playing field between merchants and consumers. Chargebacks safeguard consumers against identity theft, billing errors, defective products, undelivered orders, merchant fraud, and even straight-up lousy service. In this sense, they are a good thing (we probably all know what it’s like to get screwed by a business).

But chargebacks are also a significant and ongoing threat to a company’s revenue, especially in an age of E-commerce when chargeback fraud—often weirdly called “friendly fraud”—is unsurprisingly on the rise.

The Chargeback Cycle

Fortunately, credit card networks take a rigorous approach to defining legitimate chargebacks, and it’s even possible for merchants to fight back (in a process called representment described below).

Here are the steps in the credit card chargeback cycle:

Customer Submits a Chargeback Request

The first step in the credit card chargeback cycle is the moment when a customer actively disputes a credit card transaction. To dispute a credit card payment, the customer must submit a chargeback request with their card issuing bank or financial institution.

Issuer Assigns the Chargeback a Reason Code

Once your customer’s card issuing bank receives the chargeback request, it reviews the request and assigns it a “reason code,” which identifies the rules that will guide the rest of the credit card chargeback process.

The Issuer Denies or Approves the Chargeback

The issuer then evaluates the reasons why the cardholder wants to dispute the credit card transaction. If the issuer judges the cardholder’s claim to be illegitimate, the chargeback process comes to an end without any additional actions.

If the issuer believes the cardholder’s chargeback request is legitimate, however, it notifies your business’s payment processor of the chargeback, and your acquiring bank reverses the transaction, withdraws the relevant funds from your business’s merchant account, and returns them to your customer’s issuing bank. The issuer then credits those funds to the cardholder’s line of credit (in the case of a credit card transaction) or bank account (in the case of a debit card transaction).

You might be wondering how that last part—the withdrawal of funds from your merchant account—is even possible. That money is already yours, right?

Technically, no. This is because accepting credit card payments is a loan. As we discuss in our guide on Understanding Credit Cards, when you accept a credit card payment you’re receiving a loan from an acquiring bank until the time when your customer can no longer dispute the charge (up to a year or more depending on the card type and brand).

Typically, you work with that acquiring bank through your credit card processor or “payment processor” (these are equivalent terms), instead of directly, but in any case it amounts to the same thing. The acquiring bank provides the merchant account, and the merchant account acts as a “pass-through” bank account where the real funds from a credit card transaction sit until a chargeback is no longer possible. The acquiring bank takes responsibility for those funds.

So, if a chargeback happens, the acquiring bank has to pay up. And that means you have to pay up, too.

Chargeback Representment

When a chargeback happens, your business is at a crossroads. You can simply accept the loss (along with paying the chargeback fee that comes with it), or you can attempt to recoup your losses if you believe you can prove that your customer’s chargeback isn’t valid.

Credit card networks like Visa, Mastercard, Discover, and American Express provide merchants with a way to dispute chargebacks. This stage in the chargeback cycle is typically called representment.

Representment involves gathering evidence that a disputed transaction was valid and “re-presenting” the chargeback to your customer’s issuing bank.

Representment takes place in the following general stages:

The Merchant Gathers Compelling Evidence

To dispute a chargeback, you’ll need to gather what the industry called “compelling evidence” against the chargeback claim. What counts as compelling evidence? That depends on the reason code given as part of the chargeback claim.

Your Acquirer Disputes the Chargeback

At this stage, your acquirer or payment processor takes the compelling evidence your business provides and re-presents the chargeback to your customer’s card issuing bank.

The Issuer Accepts or Rejects the Evidence

The issuing bank then evaluates the evidence against your customer’s chargeback claim. If the issuer believes the evidence presented invalidates your customer’s chargeback claim, the issuer will transfer the funds from the credit card transaction back to your business’s merchant account. If the issuer doesn’t find the evidence compelling, however, the chargeback process typically comes to an end with your business on the losing side.

Chargebacks Fees

Every chargeback is a loss for your business. This is because you’ll pay chargeback fees even in cases where your business successfully re-presents a chargeback. This is in addition to the regular credit card processing fees you already paid for the disputed transaction—money your business won’t get back.

Chargeback fees are service fees paid to your acquiring bank or payment processor to cover their administrative costs while handling a chargeback. Chargeback fees typically fall within the range of $15 and $100 (a pretty large range!), with higher-risk merchants tending to pay higher fees.

Chargeback Monitoring Programs

To make matters worse, every chargeback is a small ding on your business’s reputation in the card payment industry. And, if your business consistently experiences a lot of chargebacks, credit card networks might start to view you as a high-risk merchant and enroll you in a chargeback monitoring program.

For instance, Visa monitors and evaluates merchants using a chargeback threshold combined with a chargeback ratio. Basically, you’re only allowed 100 chargebacks per month (the chargeback threshold) and chargebacks-to-sales ratio of 1%.

Since even successfully disputed chargebacks negatively impact your business’s chargeback-to-sales ratio, it’s important to prevent as many chargebacks as possible.

Preventing Chargebacks

The reality is that a merchant isn’t likely to successfully fight back against all (or even most) chargebacks, so your best strategy is to prevent chargebacks from happening in the first place.

Here are 3 of the most tried-and-true ways to avoid credit card chargebacks:

- Focus on providing good customer service.

A lot of chargebacks stem from dissatisfied customers. Although technically customers are supposed to try to redress their grievances by first contacting and negotiating directly with the merchant, many consumers won’t take that step if they don’t view your business as open to communication and complaints. - Follow your payment processor’s rules for each transaction.

Maybe some rules are made to be broken, but your payment processor’s rules aren’t among them. If your payment processor wants you to verify a signature, check a card’s expiration date, or enter a security code from the back of the card, do so. Your payment processor may even have special rules for card-not-present transactions (such as transactions that take place over the phone or online) because of their increased risk. - Use a recognizable payment descriptor.

Your customers are more likely to dispute a card transaction if they don’t recognize it on their monthly statement. To lessen the chance of that happening, make sure your business’s payment descriptor, which is what appears on your customer’s monthly statements, is clear and easy to identify.